But I’ve been most intrigued by her declarations of love for a very personal piece of her Parisian life — the neighborhood and, more specifically, the street, she has called home for the last decade. Her new book “The Only Street in Paris: Life on the Rue des Martyrs” spoke to me not only because I know the street well but because I have a similar attachment to my own neighborhood, my street, the characters that make up its narrative and the energy they exude.

Part memoir, part travelogue, Sciolino’s book is a magical stroll through one of the city’s most coveted streets, brimming with artisans old and new who have, somewhat unwittingly, ushered in a sense of renewal in the face of globalization. With captivating storytelling and images photographed by her daughter, Sciolino adds something new and fresh into the Paris expat/memoir idiom.

To whet your appetites, she has graciously supplied an excerpt from the book that has not been featured anywhere else. Below: “The Meaning of Martyrdom”. Bonne lecture!

—

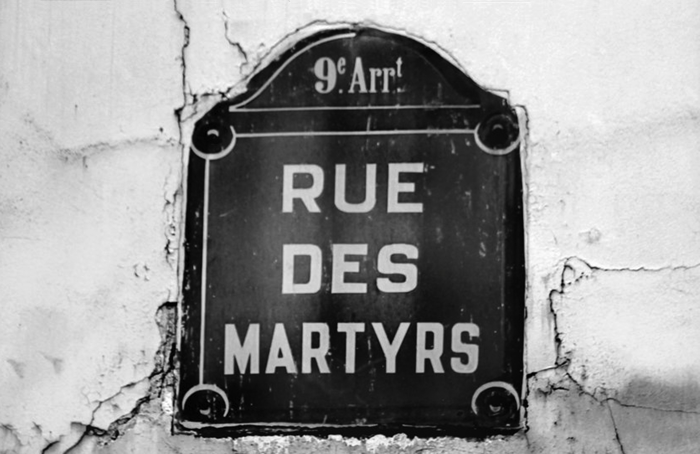

Paris has more than sixty-two hundred streets, boulevards, avenues, and passages. Their names fall into several categories: kings (Henri IV, François I), American presidents (Wilson, Roosevelt), military victories (Iéna, Aboukir), important dates (September 4, after the day in 1870 when the Third Republic was created; November 11, after Armistice Day, marking the end of World War I), trades (bakers, drapers), about 175 saints (Jean, Paul, Georges), cities of the world (Tehran, Cairo, Rome), and the eccentric (Street of the Cat Who Fishes, Street of Bad Boys, Street of the Warmed Up, Street of the White Coats). “Street of the Martyrs” fits into the last category.

So who are these martyrs who deserved a street to be named after them? They seem to be everywhere. A pharmacy, a pastry shop, a bistro, a men’s clothing boutique, a crusty bread and a mom-and-pop grocery store on the rue des Martyrs all have the word “martyrs” in their name.

The explanation about the martyrs turned out to be a long and complicated tale.The street’s martyrs are Saint Denis and his two companions, Rusticus and Eleutherius, who lost their heads for preaching the Christian gospel.

There were no contemporary histories of Denis, only interpretations of his life over the centuries, none reliable. The dominant legend is set in the third century, when France was part of the Roman Empire. The pope sent Denis to what is now Paris to convert the pagan population to Christianity, at a time when Christians were a marginal cult. Denis built a church, hired the clergy, smashed pagan statues, preached the Gospel, and made miracles. In modern parlance, he was a rock-star missionary.

Alarmed they were losing ground to Jesus, pagan priests imprisoned the three Christians for refusing to accept the divinity of the Roman emperor. Many versions of what happened next appeared over the centuries. Denis and his companions refused to die, despite enduring a variety of tortures in prison. The most gruesome account of the tortures is described in an elaborate but fanciful ninth-century biography commissioned by Emperor Louis the Pious, the ruler of the Franks, and written by Hilduin, the abbot of the royal abbey of Saint-Denis outside of Paris. Hilduin cared less about the truth and more about the creation of a cult of a patron saint to beat all others. In his telling of the tale, tabloid-style, Denis and his companions were beaten, roasted on a bed of iron, locked up with starving beasts, trapped in a blazing fire, and tortured on crucifixes.

As happens with martyrdom, the trio’s luck ran out. To ready them for death, God sent Jesus and a multitude of angels to give them Holy Communion in prison. Then soldiers led them far from the city center, halfway up a hill north of the Paris city limits to Montmartre. They stopped before the Temple of Mercury at what is now the rue Yvonne-le-Tac, near the top of the rue des Martyrs. There, the executioners cut off their victims’ heads, using blunt axes to maximize their suffering.

Still, Denis held on. In a great miracle, and despite being ninety years old, he raised himself back to life. He cradled his head in his long white beard, washed it in a fountain, and carried it four miles north to where he wanted to be buried, all the while accompanied by a choir of singing angels. But the resurrection was only temporary. When he reached his destination, he surrendered to death once and for all.

Denis became not only one of the most revered saints in Christendom but also the patron saint of France. French kings and future saints, including Bernard, Thomas à Becket, Thomas Aquinas, Joan of Arc, Francis de Sales, and Vincent de Paul paid homage by walking in Denis’s footsteps up the route that is now the rue des Martyrs. It may be illogical, but the devout pray to him to relieve their headaches.