Photo Courtesy of pvcpvc

I grew up in a family obsessed with talking and thinking about food and because of that, I developed a very food-centric mind. As I lay in bed, my mind drifts in and out of thoughts about the following day’s breakfast – the usual mixture of cereals with sliced banana – and even lunch, visualizing myself hungry around noon or one and what I’d be in the mood for. It’s exhausting. But I wasn’t always this consumed by food. It really started when I first came to Paris.

Young and with an extremely effective metabolism, I came to the city where pastries of the gods reigned supreme and almost immediately lost a once stalwart self-control. Beckoning from every corner bakery with their creamy buttery scent and melted chocolate, dessert became a twice daily indulgence I couldn’t resist. I had never felt so powerless in the face of piping hot baguettes, and flaky pain aux amandes. And it was at this time that my body turned on me.

Growing up, I was always one for second-helpings, particularly on pasta night for which I waited impatiently each week. Even after two (sometimes two and a half) plates, I miraculously always had room for an ice cream sundae – the preeminent dessert of my childhood. But that’s where it ended. I went on with my evening, most likely to write some kind of angst ridden poetry and read over my crushes love letters. My mind wasn’t consumed with images of food, restaurants I wanted to try nor was I anxious about eating enough at one meal so as not to be ravenous a couple hours later.

Conveniently, the summer I met my husband was also the summer my metabolism came to an unpleasant screeching halt. The girl who once shamefully ate fast food and copious amounts of carbohydrates without every gaining a pound was now in a position to evaluate her eating habits and slim down. I gained 10 pounds over the course of 7 weeks and I have only myself to blame. I was anything but gastronomically adventurous before my trip to France and left with a more than just a cultivated palette. I was hyper aware of the changes I was experiencing and just as self-conscience. It took almost 2 years to return to my pre-dessert-binge weight but I couldn’t shake the obsessional food thoughts or the unflagging cravings for everything with little nutritional value. It was a battle because I was seemingly unable to control my appetite, eating well after I was full and sneaking little bites as soon as I sensed hunger pains.

I tormented myself with thoughts of what I should and shouldn’t be eating, opting for non-fat products and sugar substitutes to ease my mind. I was convinced I would have had an easier time getting healthy in the States, where there isn’t a dearth of healthy food options. France was the problem, what with their fatty meals and strategically placed bakeries to crush any control I might have had left. And then I started reading and getting wise.

Our obsession with food, whether we are underweight, overweight or somewhere in between, is not really about a lack of self control at all, as I used to believe, but rather about conditioning, which his exactly why I don’t trust the food industry and neither should you. They’re sneaky, mendacious and driven to turn us all into, what David Kessler calls, conditioned hypereaters (those who are conditioned to seek continued stimulation as a result of chronic exposure to highly palatable foods).

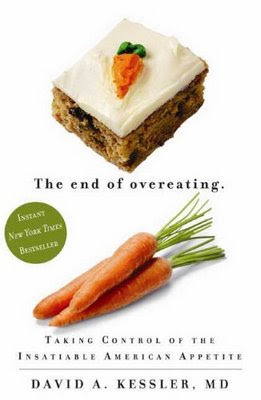

As I lay on the beach in Corsica, I was transfixed by Kessler’s book “The End of Overeating: Taking Control of our Insatiable Appetite”. With the sand getting stuck to my thighs and the blotchy red marks from the sun beginning to form, I eagerly turned each page feeling simultaneously horrified yet reassured by Kessler’s research about how food manufacturer’s have brainwashed us into consuming endless amounts of salt upon fat upon sugar upon fat, leaving us powerless in their wake. He went digging in dumpsters after hours outside popular American chain restaurants searching for ingredient labels on boxes that would prove his theory that certain foods cannot be resisted because they’re not made to be.

His conclusion is that foods high in fat, salt, and sugar alter our brain’s chemistry in such a way that we feel compelled to overeat. The food industry knows there is a disjunction between hunger and satiety and capitalizes on our weakness – hence the term “conditioned hypereating” –

“The eating is often excessive, driven by motivational forces we find difficult to control…it works the same way as other ‘stimulus-response’ disorders in which reward is involved. Such disorders are characterized by a high degree of sensitivity to sensory stimuli, and they typically lead to a perceived loss of control, an inability to feel satisfied, and obsessive thinking”

Kessler says that instead of satisfying us, the excess of salt, fat and sugar mixed together in the majority of restaurant food stimulates our brains to desire more. So whether or not we are strong-willed, we are screwed from the second we sit down. So far this has been particularly true for Americans and a rapidly growing number of Brits but as meal patterns are changing in France, so are their eating habits and choices. With sugar in McDonalds hamburger buns, Japanese shrimp rolled in mayonnaise, fried in tempura batter, then rolled again in mayonnaise, and enough sugar in a Starbucks Strawberries & Crème Frappuccino to surpass the calories of a personal sized pepperoni pizza, most of us aren’t even aware of the deleterious quantities of fat, sugar, and salt in the food we’re marketed.

Because an industrial pack of cookies at 100 calories is STILL a cookie. Photo credits: Kharizmarae82

Kessler’s book isn’t about dieting, far from it. It’s about understanding our food consumption from all angles and learning how to combat the “conditioned eating” that the food industry has forced upon us over time. It’s a vicious cycle – the FDA creates legislation to make some of the industries tactics more transparent yet allows for loopholes that, in the end, perpetuate the same problem. If we’re increasingly unhealthy and subsequently requiring more and more medical attention/intervention, what is the solution?

Accurate food labeling is a start but what about taxing junk food? Increasing the cost of high-fructose corn syrup? If we can’t rely on change to come from within the industry, be it voluntary or legally enforced, the change has to come from us, from our perception. This, of course, takes more effort on the part of the consumer, but it’s the only way to fight back. One of the suggestions Kessler offers is to make a cognitive shift as a country and change the way we look at food.

“We did this with cigarettes. It used to be sexy and glamorous but now people look at it and say, ‘That’s not my friend, that’s not something I want.’”.

We need to do the same thing with food, looking at the unhealthy foods that haunt and seduce us as bad, creating negative associations to send the signal to our brains that the huge plate of (insert dish here) is not something we actually want.

It’s not about deprivation – that only heightens the way the brain values food, (which is why dieting doesn’t work). As I tried to convey in Part I about Nutella, I’m not suggesting we boycott the sweet and salty foods we love altogether. I’m simply saying that there’s a reason it’s a challenge to stop buying that bag of chips each time you go to the supermarket and a battle not to stop at the Starbucks you pass on your way home from work everyday for your favorite mocha latte, and that reason is more scientific than we realize.

Kessler’s book not only opened my eyes to the greed driving the food industry and how their strategies have taken their toll on our health but also reminded me that we shouldn’t blame ourselves entirely for our inability to control our deepest food cravings. More likely than not, it’s got little to do with control at all.